ArtSlant / Interview

Brussels, Aug, 2012 - I met up with Belgian artist Maarten Vanden Eynde as he installed the finishing touches on his latest show, The Museum of Forgotten History XXX, at MuHKA in Antwerp. The cacophonous sounds of Jimmie Durham’s lively and exhaustive retrospective echoed from the floor below, linking the two exhibitions, which could not complement each other better. While Durham questions naturalized ideas of geography, nationality, ethnicity, and materiality, Vanden Eynde deals in epistemology, throwing into uncertainty the notion of scientific knowledge and historical accuracy in the past, present, and future. These are artists who remind us, in their own unique vocabularies, to take nothing about the world we think we know for granted.

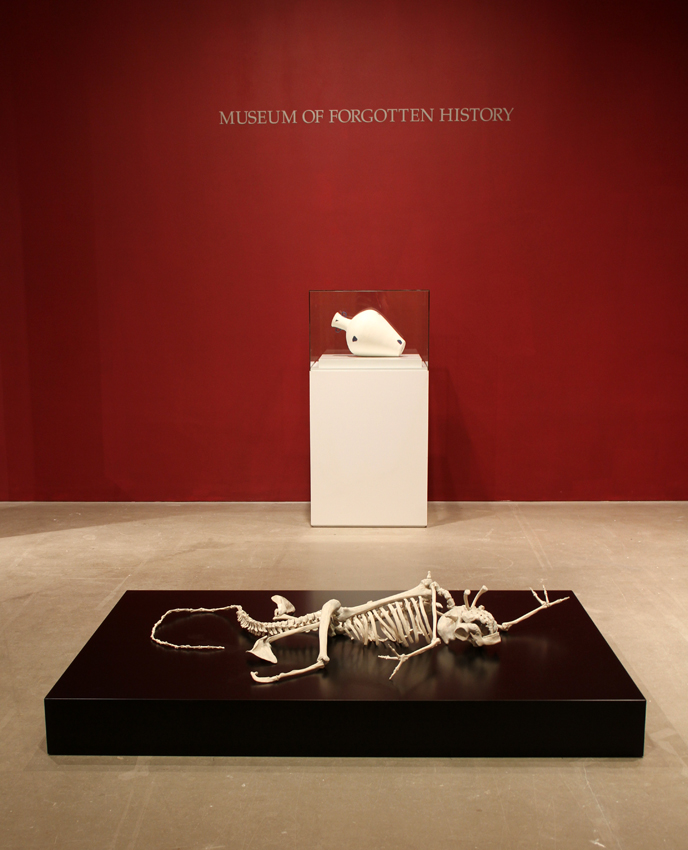

In The Museum of Forgotten History, Vanden Eynde sets his own artwork in dialogue with diverse works from MuKHA’s collection. The exhibition masquerades as a museum in the far future, one that assembles ancient artifacts, negotiating significance and piecing together history.

The notion of the present as the past in the future – breathe in, say it again, slowly – is central to Vanden Eynde’s practice, which imagines a distant future in which all that remains from today are mundane objects like Ikea teacups, nuts and bolts, and plastic takeaway containers. What deep meaning will future archaeologists of our planet ascribe to these seemingly banal objects?

In addition to the show at MuHKA, Vanden Eynde’s Plastic Reef is part of this summer’s Manifesta 9. The artist collected plastic debris from four of the five ocean gyres – the giant concentrations of plastic waste often mischaracterized as “plastic islands” – and melted it to form this growing sculpture.

Andrea Alessi: The Museum of Forgotten History presents an incomplete picture of our future past. There are a lot of missing pieces, a lot of leaps of faith. For some it might seem a strange representation of the contemporary, but perhaps it is no stranger than how we piece together our physical world and histories today.

Maarten Vanden Eynde: Science has been doing this since the beginning – working with small fragments of information to create a bigger picture. As they fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle, the overall image can change depending on what they’ve found. That’s the whole basis of The Museum of Forgotten History – it’s the subjectivity of history and history writing. It’s constantly being altered and changed, and because it keeps changing, it puts in question everything you know right now; it might change when we find something else.

AA: As your work demonstrates, it can be really funny as well.

MVE: It’s very humoristic and it creates a lot of possibilities. It’s not just: “Oh no! History is very subjective. We don’t really know anything anymore!” That’s the whole beauty of it. History is written by subjects who change the cource of history every time they decide to do or not do something. All six billion can do that. It could be your little diary that is the last thing representing this time period. Something small can become really big.

AA: So is your work a critique of institutions and disciplines as the arbiters of knowledge?

MVE: Not the institutions per se, but what they have as an image of the carriers of truths. With my invented science of genetology, I’m definitely not mocking science – I’m a big fan of science. It’s just a missing department in current scientific knowledge. Instead of saying that the game isn’t valid, I rather want to play in the same field.

AA: With Plastic Reef you’re drawing awareness to an environmental problem. Do you consider your work to be a form of activism?

MVE: It’s always problematic for me to have these categories because I think I fit into a lot. If you ask me “are you a conceptual artist?” I will say, “yes, I am working with concept.” The same applies to whether I’m an ecological artist or activist. I’m all of it, but that doesn’t exclude other functions or other ways that I’m working. I also consider myself an archaeologist. I’m not really working as an archaeologist in the field of archaeology, but I’m approaching objects in a similar way.

AA: You give some visibility to plastic pollution. In an ideal world is there something you would want to accomplish by doing that? Like encouraging people to consume less?

MVE: Definitely. In general I think wanting less is something that humans can benefit from. And more specifically, especially with plastic, it would be ideal if people realized the material features of this invention. Concerning use, it’s throwaway culture object number one, but it stays in the natural environment the longest. Chances are that it will constitute the last remnants of human civilization although we only use it for a brief second.

AA: Is Plastic Reef still growing?

MVE: It is. I’ve been to four of the five gyres [of plastic in the ocean] and now the reef is 4.5 by 5.5 meters. I definitely want to close it off. This summer I will go to the Indian Ocean gyre and somehow finish it. The final act will be a publication I’ve been working on, which will probably be called Plastic Reef, but it’s more focusing on anything that relates to plastic: the geopolitical complications of recycling plastic, the production of plastic, history of plastic. All these things will come together.

AA: Do you think of the work as recycling?

MVE: No way is it recycling! I’m just replacing and actually enlarging the problem. It’s the most polluted work I’ve ever made. It’s talking about pollution and actually it’s making it much worse. First of all, I fly to all these places. I fish the plastic out and have it shipped back here, which means another flight. And then I melt it, which releases toxic fumes. I basically just take it from one place, melt it together, then have it in a different place. But it doesn’t solve anything practically. In a direct sense, it works really well as a visual illustration of the problem and of the phenomenon, but it’s definitely not recycling.

AA: Talking about how plastics are going to last forever – do your projects drive you crazy? I can imagine walking down the street and seeing things everywhere and wondering about the possible future history for those objects.

MVE: Yeah, that’s the difficulty with polyhumans who are interested in almost everything! The whole scientific field ranges from philosophy to cosmology to geology to zoology… They all relate to what I’m interested in. It’s hard to go on holiday.

AA: How do you choose what’s important when you’re thinking about objects to preserve, like the Ikea cup or the chihuahua footprint?

MVE: It’s very organic. Most of the Ikea works I made after 2005 when I was doing a residency in Rome and I read a really tiny article in the newspaper which said that the Ikea catalogue became the most printed book in human history, surpassing the Bible for the first time ever.

AA: That confers importance, doesn’t it?

MVE: Exactly. I was so shocked about it. Also about the fact that the article was so small. I would put it on the front page! That’s a major achievement in human history! It’s just mind blowing. And so then I started thinking okay, in the far future, if archaeologists or scientists are digging in the ground and arriving at our current society, most likely they will find something from Ikea, since it is the most printed book ever and everybody has Ikea shit in their houses. And I decided to lend history a hand, so I climbed over a fence of an archaeological site in the heart of Rome and buried a little Ikea cup. In the same period I also broke an Ikea teacup and went to the restoration department at the archaeological museum in Rome. We restored it together, leaving out a few pieces. The vase in this show is a follow up, a more extreme version of the same cup, where the restoration arrives at an incorrect shape. So it depends on what you encounter. While working on a project in Hollywood, I saw these footprints in the concrete. They could have been from a chihuahua or a skunk or whatever; I decided chihuahua.

AA: You clearly have so many interests. Did you always want to be an artist?

MVE: Not necessarily. My mom is also an artist, so from an early age I understood what it was. But at the same time, I wanted to be sure of having a certain income, so I started as a graphic designer, but it only lasted for two years. And then I remember going to the open studios at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. They had a direction that was called “free direction” and I walked through those studios and I was like “Wow! I want to do that!” I mean, there was a guy who cut open a carrot, removed the core, and flayed open the skin like it was some kind of animal. In another room a guy was standing on a chair, pouring out his cup of coffee on a piece of paper and seeing how the stain was going to develop and I was like okay, this kind of freedom I want to have!

AA: Now you use a lot of writing as well. Do you consider your writing art?

MVE: Some is obviously more than others. I have written some columns that are not about art. But basically writing is just a different medium to talk about the same thing. My writing usually circles around to the subjectivity of history and how in the possible future we will look back to the present.

AA: I want to ask a little bit about the relationship between science and art. I think art is absolutely influenced by science, but I don’t think there’s necessarily an equal two-way dialogue. I feel like art is influenced a lot more by science than science is by art. Maybe you can argue that?

MVE: Yeah, I could make a case about that.

AA: Science is a flexible, nebulous body of knowledge, as well as a process. Science and technology are often conflated. Artists are using a lot of technologies that scientists use, but that doesn’t make it science.

MVE: It’s probably not in balance, but I know that quite a few scientists are using artists to look at things in a different way, and are using things artists made in their own research. There are a lot of programs that connect artists with scientists, and I don’t know who benefits the most.

I’ve done a project with NASA mathematician Martin Lo, the inventor of the Interplanetary Super Highway. He was kind of stuck with his theory on dark matter, and he asked if I could think of a visualization of the invisible. I didn’t manage to grab the concept. I battled with it for a few months then decided to make it into a much bigger project, inviting artists to think about the same question. It became quite a big exhibition in Amsterdam.

AA: Smooth Structures at Smart Project Space?

MVE: Yes. I’m not sure if in the end he could use something in a practical sense, but I’m sure that he was inspired about some of the ways that artists looked at the problem. There is also David Kremers, an artist who is almost eaten up by Caltech. Research groups from different fields book him and they talk about what they’re researching. And he somehow manages to put it into the framework of reality for everyone. A lot of these concepts are absolutely far-fetched because they’re thinking of the unthinkable. And usually it’s flying so high that they can’t bring it back down to earth. And he manages to do it. Everybody appreciates his influence on their research so much they calculate a portion of the budget for him.

AA: Okay. You’re making good a case here.

MVE: It’s not only in science. I’m used a lot as an external consultant for other kinds of meetings and think tanks. I worked with the insurance company Generali Group, because they think a lot about possible future scenarios and how it might influence their current business model. It involves all kinds of things that can happen in the future, from water levels rising to clean air to the better ability of people to do their own medical research on the Internet. So we created these future scenarios and linked them back to their current business model, anticipating possible future changes. It’s super interesting, but I’m not making something physically. I’m just brainstorming with them.

AA: It underscores the interdisciplinary value of creativity.

MVE: Yes. I also did a workshop for one of these millennium goals to halve child poverty by 2020. This one Belgian minister invited people mainly from the field of child poverty to participate. I was a sort of wild card, to help open up discussion and think of things they wouldn’t. I think artists are often used as a kind of open mind source. I like doing that a lot. I absolutely think the art world is too small. There’s so much more going on outside of the art world and that is equally valuable and interesting.

AA: Yeah, to just make art that references art –

MVE: – it’s the art that I dislike the most. Art about art is like a loop in a loop. Aaah! It’s already so small. You talk about this small world that almost nobody knows about. Then you talk about works or artists that almost nobody knows about and it’s all so self-focused. I don’t like that. I prefer to have a wide-open lens looking at the multiverse and the God-particle at the same time. There are so many interesting and beautiful things around, why limit yourself to art?